|

| Fun with fungi. |

This is a personal epilogue to the nine-part series just concluded about Baudoinia compniacensis, the whiskey fungus. If you have not read it and are interested, the series starts here.

I became aware of Baudoinia about 30 years ago, when I began to spend a lot of time at distilleries. I noticed it first at Jim Beam in Clermont. The black-trunked trees caught my attention. I had never seen bark that black. I thought it might be some Kentucky tree species with which I was unfamiliar. So I asked, which got a laugh.

They called it "the whiskey fungus." I never heard any other name for it until I dug into the research. Baudoinia is its new name, as mentioned in the series. The name I first encountered was Torula compniacensis, at which point I decided to keep calling it "the whiskey fungus."

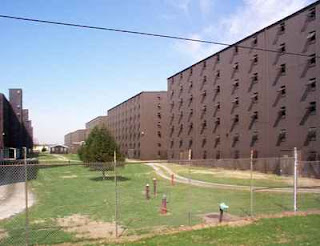

Only after my inquiry about the trees did I begin to notice it on the sides of warehouses and other buildings. It usually appears darkest at ground level and gets lighter the higher on the wall it goes. It looks like dirt. Most people think it is dirt. I did. Most people don't like dirt, but they aren't afraid of it.

I had a friend back then who lived next to the Barton 1792 Distillery in Bardstown. Her house was literally the first one outside the old main gate. She had some on her garage. She said a couple times a year she called the Barton office and they sent someone over with a power washer, no charge.

These days it's not so simple. "Cleaning assistance, which we did, is more complicated than it appears," a retired bourbon company executive told me. "We had serious concerns that some of the houses would fall over from pressure washing. We had people sic their dogs on the cleaning crews," he said. "Just getting releases signed was a nightmare."

I never heard anyone express concern about it as anything other than a mild nuisance until 2012, when the trouble in Louisville began. That story, especially the Stitzel-Weller part, is the throughline for the series.

As I read about the Metro Louisville Air Pollution Control District citation that started the ball rolling, I thought back to a lunch I had with Bill Samuels Jr. in 2003 or 2004, at Kurtz's in Bardstown. (I had a hot brown, I think Bill had fish.) As we were finishing, Bill mentioned he was on his way to Louisville for a meeting with that agency, or its predecessor, or maybe the federal EPA. I asked if something was going on. He said no, he had to meet with them every couple years to review the distillery's emissions profile. Ethanol vapor was mentioned but carbon-dioxide released during fermentation was usually a bigger concern.

The point of that memory is that distilleries routinely interact with applicable government monitors and regulators about all relevant emissions issues. Despite all the romance attached to them recently, distilleries are factories. Their operations impact air and water quality and always have. Baudoinia didn't suddenly come out of nowhere in 2012. Nobody is hiding anything about Baudoinia from the government or the public. I suspect that 2012 citation was made in error by someone unfamiliar with the industry.

I am about as far from a scientist as you can get, so my understanding of these things is a layperson's, but a layperson who has followed the subject over a 30-year period. The literature is not extensive and I have read most of it. The series just concluded covers the subject as thoroughly as possible.

Fungi play an important role in bourbon-making. In my 2014 book, Bourbon, Strange, I wrote about Aureobasidium pullulans, one of several fungal species that help release flavor compounds in white oak during natural seasoning. To quote me: "Carried by air, the spores land and send out roots (hyphae) that penetrate into the wood structure, where they release hydrogen peroxide. This natural bleaching and oxidizing agent helps break down the wood chemically, softening tannins and caramelizing hemicellulose among other salutary effects."

Other molds follow Aureobasidium and continue its work, but not Baudoinia. It's useless. It doesn't do anything. It can't even caramelize a little hemicellulose. It is neither good nor bad, just ugly.

Fungi are part of our environment. Very few are dangerous. The mushrooms on your pizza? Those are fungi too. If you got them at the grocery they're probably fine. If you picked them off a log by the creek behind your house, maybe not.

But molds, not mushrooms, are the fungi that scare people these days and Baudoinia is mold. If you would like to know more about the assorted fungi popularly known as mold, the United States Environmental Protection Agency has a wealth of mold resources.

In Kentucky and Tennessee, Baudoinia is the mold that has people's teeth on edge. "It may cause cancer also, which they don't care to admit," is a recent comment posted in social media, in response to my Baudoinia series, by a person who, ironically, is living proof that his fear is misplaced. He and his similarly aggrieved Kentucky neighbors have lived their entire lives surrounded by Baudoinia, exposed to it more than just about anyone else in the world.

The Kentucky communities where whiskey is made are about 250 years old. Baudoinia has been conspicuous there for at least 150 years, which is when they started to fill warehouses with thousands of barrels of aging bourbon. If Baudoinia could hurt you, the evidence would be there, in central Kentucky, or south-central Tennessee, or in Scotland, or Cognac, or Lakeshore, Ontario. There is none.

People keep saying, without evidence, that Baudoinia is dangerous. It is not. They keep saying it hasn't been studied. In fact it has been studied extensively, by multiple scientists, in Europe and the Americas, over that 150-year period. It has some novel characteristics, but nothing remotely dangerous. The evidence cited for its danger is its mere existence. "Something that looks that bad can't be good for you," is about as far as it goes. "It's killing our trees!" the Tennessee litigants claim. Something may be killing their trees, but it's not Baudoinia.

So, why do people freak out about Baudoinia? As I theorized in the series, in the 1990s, the danger of toxic molds entered the public consciousness. Because Baudoinia is unusual, and unfamiliar, many people assume it must be harmful. Add to that its connection to whiskey, to which some people morally object. A fungus that feeds on whiskey vapors? Get thee behind me, Satan! Other objectors know it's not dangerous, but are embarrassed to whine about a little dirt on their lawn furniture, so they conjure up a hideous, hidden threat. Some people just want attention.

The narrative that multinational poison merchants are callously polluting rural communities with dangerous emissions, and spreading disease-causing mutant plants, is catnip for the conspiratorially-inclined.

As far as that goes, we're all living in a petri dish, but we're not talking about flesh-eating bacteria or brain-eating amoebae or what have you. Baudoinia is basically mildew. Living near a whiskey plant and complaining about Baudoinia is like living at the beach and complaining about sand. We've all got bigger things to worry about.

Don't you realize it's that phone you're staring at right now that's going to kill you?

Finally, in some of the worst timing ever, Kentucky's distillers have just pushed a bill through the legislature to eliminate the hefty 'barrel tax' that goes directly to the county governments where maturation warehouses are located. Taking millions out their budgets has those governments up in arms, vowing to stop new warehouse construction citing, among other issues, public health concerns about Baudoinia.

Whiskey makers, both legacy and new, want to make their products in Kentucky and Tennessee for many reasons. Most important is the market's preference for Kentucky bourbon and Tennessee whiskey, but they also like being where their industry's idiosyncrasies are understood and appreciated. Distillers and politicians seem determined to screw that up.

I have written about Baudoinia before. I have written about it so many times I can type Baudoinia without checking the spelling. Most of this series was originally published in my newsletter, The Bourbon Country Reader. If you like this sort of thing, feel free to subscribe.

I posted this series because when this subject pops up, it usually is because a new distillery or maturation facility has been proposed. The local media does their best, as do concerned community members, but if they go online to do research most of what they will find is hot but not well informed opposition that is little more than a typical not-in-my-backyard reaction to any development someone views as unfavorable to their personal interests.

I also posted it here on my blog because a 7,000-word article about an obscure fungal species is not the sort of thing very many editors are interested in, even (or perhaps especially) at the whiskey publications. (My view stats for this series tells me they're right.) You won't get the full story from any of the companies or industry trade associations either. That's probably a mistake.

I admit to being pro-bourbon but otherwise have no axe to grind. I was interested in the subject because of my interest in bourbon so I did a lot of research about it. This is what I found out.

I hope, if you got this far, it was useful.

5/21/23: Since this was published, many people have asked if there is a technological solution. Yes, there is. It's this.