|

| Red Likker, a novel by Irvin S. Cobb (1929) |

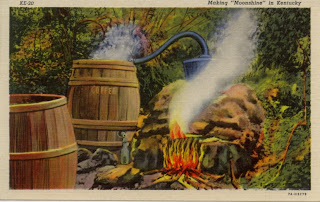

Almost a century ago, a spectacular and suspicious fire at a whiskey warehouse in Kentucky inspired a popular author to write a fictional history of bourbon.

Irvin S. Cobb was an American author, humorist, and columnist who was born in Kentucky but lived most of his life in New York. He authored more than 60 books and 300 short stories. His novel, Red Likker, was published in 1929. It concerns a Kentucky family named Bird and follows them from their pioneer beginnings through Attila Bird’s service in the Civil War, on the Confederate side.

The Birds are whiskey makers and after the war, Colonel Bird becomes a successful Kentucky distiller. The story ends with Prohibition and its climax is based on actual events that occurred at the Forks of Elkhorn Distillery, then owned by R. A. Baker and Thomas Hinds. That site today is a bottling and maturation facility for Beam Suntory. Some people remember it as the Old Grand-Dad Distillery.

Cobb’s Colonel Bird is a man of high principles, brought sharply into focus by the duplicity of everyone around him. He is nearing the end of his long life. The government won’t allow him to sell the whiskey maturing in his warehouses, a product that was legal when he made it. He is approached by scoundrels willing to buy it, but who also threaten to steal it if he won’t sell. In the end he burns it all to the ground, after first cancelling his fire insurance because, you know, principles.

The real Forks of Elkhorn fire occurred on July 21, 1924. It destroyed a federally-licensed concentration warehouse that apparently held both case goods and maturing barrels, as one newspaper described “bottles, barrels and cases popped all Monday night in the dying flames.” The Lexington Herald reported that 2,200 cases and 1,500 barrels of whiskey were destroyed. Two additional warehouses were saved.

Most of the maturing whiskey that was lost belonged to Mary Dowling. She had made it at her Waterfill & Frazier Distillery in Anderson County but was required by the Feds to move it to Frankfort following her arrest for illegal sales. The remainder was owned by the distillery. Although faulty wiring appeared to be the cause, there was a report that the insurance had been cancelled just a few days before the fire occurred, which inspired Cobb’s climax. Baker and Hinds subsequently sold the facility to the Paul Jones Company, best known for their Four Roses brand.

The fire occurred just as whiskey interests were arguing for a reduction in fire insurance rates, since there was “virtually no fire risk” in the government’s concentration warehouses, so they claimed. Three days after the fire, the Kentucky Actuarial Bureau announced that no rate reduction would be granted.