|

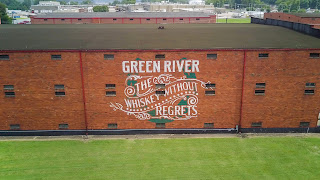

| Maturation warehouse at the Green River Distillery, Owensboro, Kentucky. |

It was announced today that Bardstown Bourbon Company is buying the Green River Distillery in Owensboro, as well as Green River's bottling, blending, and product development facility in Charleston, South Carolina. Whiskey enthusiasts want to know what it means. Mainly, it means creating a major whiskey producer from scratch, and apparently in a hurry, takes a lot of scratch, as in capital, which Bardstown Bourbon Company clearly gained access to with its sale to Chicago's Pritzker Group earlier this year.

There is a long tradition of Kentucky distilleries seeking and finding capital in Chicago. Jim Beam did it. So did the descendants of Tom Moore, whose distillery in Bardstown is today's Barton 1792. The alternative is sale to one of the major distilled spirits producers. Heaven Hill recently bought Samson & Surrey. MGP bought Luxco. Constellation owns Nelson Brothers and High West. Pernod owns Jefferson's, Smooth Ambler, Rabbit Hole, and Firestone & Robertson. Who's next? New Riff? Wilderness Trail? Sagamore Spirits? Jackson Purchase?

The majors don't buy production facilities, they buy brands, which Bardstown Bourbon and Green River don't have. After Green River adopted that name and walked away from that TerrePure rapid-aging business, they began to position themselves exactly like Bardstown Bourbon, as the best place for a non-distiller producer to create and build a brand. The hook-up was a natural.

Ample capitalization makes the new combination less dependent on contract distilling and better able to invest in brand development for its own portfolio, while socking away whiskey to mature, to use when it's ready, either in their own brands or for that most profitable kind of bulk sales.

Some people will foresee in this omens of doom. Others will gleefully chant, "glut, glut, glut."

The reality is, there is a lot of whiskey being made. That's nothing new, and not just here. Whiskey is up everywhere. We've been in this boom, by some estimates, for two decades already. Prices aren't softening. Everybody is booked up with contract work. Everybody is adding capacity. Whiskey in every maturity segment, from young whiskey going into the flavored and ready-to-drink products, up to and including once-rare 'teenagers' (anything north of 12-years-old), is available and selling, with older stuff more scarce, of course. At the moment, there are a few bottlenecks. Everybody is having trouble getting bottles and barrels. Grain prices are high because of the war, but availability doesn't seem to be a problem. Maturation warehouses are going up at a rapid clip, Buzick is busy; but don't worry, Kentucky isn't running out of land.

Bardstown Bourbon Company was a literal green field project. Nothing was there when they began construction. Green River operated as Medley Brothers until 1992 and has history back to the 19th century. It got a major re-do after Terressentia bought it. Both distilleries have been producing since 2016, and their liquid is solid, so this sale won't change anything in terms of how much whiskey is available in the marketplace.

What seems to be shaking out is we will have boutiques and bigs, that's it. All in all, business as usual. If there is anything unusual about this moment, it is the speed with which all this is happening. By it's nature, the whiskey business is used to a more leisurely pace.