|

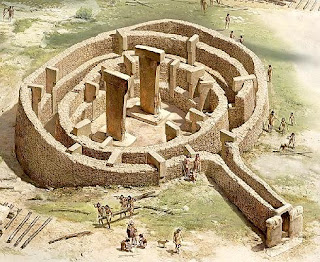

| Göbekli Tepe is a Neolithic archaeological site near the city of Şanlıurfa in Southeastern Turkey. |

Yet although rye has been around all that time, it is never the first choice for any important application. Wheat is better for bread and barley is better for beer. Because rye will grow where those do not, and livestock like it well enough, rye is always in the mix.

After 10,000 years, humans finally have figured out that the highest and best use for rye is rye whiskey.

Corn, what some call maize, is the world’s go-to cereal for distilling. Corn and rye have very different properties. Corn kernels are huge and yield a lot of fermentable material. Rye yields less alcohol even on a per-bushel basis and costs about twice as much.

For drinkers, the big difference is taste. Corn distillate has very little flavor. Most bourbons are more than 75 percent corn so most of their flavor comes from the charred oak barrel. What little taste they get from the mash comes from small grains: rye, wheat, and barley. Rye is the most used of these 'flavor grains' because it is the most flavorful, too flavorful for some palates. That's why many popular bourbons and both major Tennessee whiskeys use so little of it.

Yet even though Jack and George don't like too much rye in their Tennessee whiskey, both like it in their stills just fine. Both Jack Daniel's and George Dickel now make rye whiskey too.

Rye whiskey very nearly died out. Thirty years ago, only three distilleries in the United States (all in Kentucky) regularly made rye whiskey, and made it only one or two days per season. Today, just about everybody with a still makes rye whiskey.

The rye grain sold for distillation today is rarely a single variety. Most of it is grown in Northern Europe or Canada. Minnesota is the only major U.S. supplier.

Today, rye is planted primarily for soil improvement, grazing, or both. In Pennsylvania, for example, only about 18 percent of the rye planted each year is harvested. Most of that is used for the next year's cover planting. The rest is fed to livestock.

All of that means little of the rye planted in the United States is cultivated for its flavor characteristics. That potential is virtually untapped. So while the growing and distilling of heirloom maize varieties is interesting, doing the same thing with rye is potentially spectacular.

Rosen, a hybrid developed a century ago at what is now Michigan State, was once highly regarded for whiskey. It grew in Michigan and elsewhere for most of the 20th century, until the late 1970s. Efforts are underway to revive it, but that takes time.

The northern parts of Pennsylvania and New York once grew a lot of rye for whiskey and could again. If there is a market, the farmers will figure it out.

In Colorado, Todd Leopold found a local farmer who would grow Abruzzi rye for him. Leopold chose Abruzzi because it contains higher-than-normal levels of certain substances he believes are good for rye whiskey. Then he discovered and had built a special type of still that transfers those flavors from the mash to the spirit. The resulting whiskey is wonderful, a revelation.

Many distillers would like to work with these super-flavorful rye varieties, but would prefer to get them from Brooks or some other broker. The grain dealers aren't there yet but they're working on it.

This is just the beginning. With rye grain varieties cultivated for whiskey, stills and other equipment built to accentuate rye's characteristics, and a community of creative distillers and adventurous consumers, the possibilities for rye whiskey are limitless.

It is, potentially, another agricultural revolution, 10,000 years in the making, at least as regards the agriculture of whiskey.

In recent years I have come to prefer Old Fashioneds made with Rye. I make mine far less sweet than the usual recipe, and I find the flavor of Rye does really well with just a hint of sweetness from an orange slice, or a little OJ and some bitters. No sugar needed or wanted.

ReplyDeleteGreat article. I discovered rye close to thirty years ago from Jim Murray’s books. I’m wondering how to get a taste of the Leopoldo Brothers’ product. As a homebrewer and customer, I knew them when they were in Ann Arbor.

ReplyDeleteYou wrote, “The rye grain sold for distillation today is rarely a single species.” I think you may mean a single variety or breed. Rye is indeed all one species, Secale cereale.

Thank you. I fixed it.

ReplyDeleteIn case you haven't tried it yet, Frey Ranch in Fallon, NV makes some great rye whiskey from their own home grown winter cereal rye. Very good spirit and great people.

ReplyDeletehttps://freyranch.com/straight-rye-whiskey/

Mr Cowdery,

ReplyDeleteLast month my wife and I had the opportunity to taste the A H Hirsch Whiskey on a cruise ship. It was from the 2003 Frankfort bottling. The tasting also included a 12 year Van Winkle, a 20 year Pappy and a 23 year Pappy. We fell in love with the Hirsch!!! With our 50th anniversary only a year away, we decided to try to but a couple of bottles to share with our friends at that time. During the search, I discovered your book "The Best Bourbon You'll Never Taste" and bought a copy (2nd hand, sorry). It took 2 readings for me to get all the players straight. But once I did, we decided to acquire a couple of bottles to share at our upcoming anniversary celebration. We obtained the first bottle a couple of weeks ago and it was from the 2003 gold foil Frankfort bottling. The 2nd bottle arrived today and we were surprised (excited)to see that it is a gold wax from the April 1990 to December 1992 Lawrenceburg bottlings. Your book notes that "about eight cases" were bottled in 1992. But, is silent on the total number of 16 year cases bottled between 4/90 and 12/92. Would your records have that number....Thanks so much for your time, Greg Murray

Greg, you have the late, great Dick Stoll to thank for that whiskey. He distilled it in 1974, two years after Charlie Beam retired from Pennsylvania Micjter's, and he stayed there until it closed in 1990. He was a truly great man and a practical distiller of the highest order.

ReplyDelete