Historically, rectification was the process of redistilling whiskey to strip out some or all of the whiskey flavor elements. Taken all the way, redistillation transforms whiskey into grain neutral spirit, i.e., vodka (GNS). Historical rectifiers also used filtering, through charcoal or bone dust, and blending. They added coloring and flavoring, some of it dangerous.

The dictionary definition of ‘rectify’ is ‘to fix.’ Rectifiers chose that name and justified their practices as ‘fixing’ poorly made whiskey, to make it more palatable and marketable.

Today ‘rectification’ is synonymous with blending. A rectifier mixes a little straight whiskey (e.g., straight bourbon) with a much larger percentage of GNS, plus flavoring and coloring, to produce blended whiskey. By U.S. law, at least 20 percent of the blend must be 100° proof straight whiskey.

This is

American blended whiskey we’re talking about. The rules for blended scotch whiskey and Canadian blended whiskey are different.

Rectifiers also make vodka, gin, and liqueurs. By definition, vodka is GNS and GNS is vodka, although most vodkas producers filter the GNS in some way before bottling. Rectifiers also receive their GNS at more than 190° proof (>95% ABV), so they add water to reduce it to 80° proof. Rectifiers make gin by mixing vodka with a gin flavoring concentrate. This is known as ‘compound gin.’

Making liqueurs requires a slightly more complicated blending process. In addition to combining GNS with a flavor concentrate, liqueurs (aka cordial, aperitif, schnapps, etc.) typically add a boatload of sugar. Most liqueurs have GNS as their base but a few use whiskey. Many of today’s so-called ‘flavored whiskeys’ are actually liqueurs. (Check the label.) As such, they may contain more GNS than whiskey.

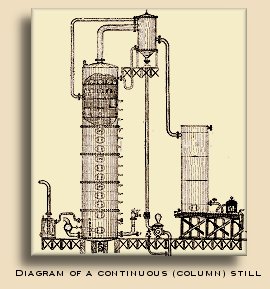

Rectified whiskey was virtually unknown before 1831. It took the introduction of the continuous still (pictured) to make redistillation, especially to or near neutrality, practical. After its introduction its popularity grew steadily. Rectified whiskey was most popular in the decades just prior to Prohibition, when 75 to 90 percent of all spirit consumed in the U.S. was rectified whiskey.

The flavor of rectified whiskey was generally lighter and less harsh than straight whiskey and because little if any of the typical blend was actually aged whiskey, rectified whiskeys were much less expensive. Rectified whiskey was also more consistent from batch to batch than all but the finest straight whiskey.

From the beginning, the makers, sellers and consumers of straight whiskey considered the rectification process disreputable.

Most rectifiers were distributors who purchased whiskey from distillers for resale to taverns, restaurants and other retailers. Their suppliers were the hundreds of small country distilleries that dotted the landscape across Kentucky and other states.

In those days, the quality of whiskey ‘at the still’ varied widely, not just between distilleries, but also from run to run within a given distillery. The quality depended on the skill of the distiller and his workers, the weather, and many other factors, probably dumb luck most of all. Even after Dr. Crow introduced the sour mash process, consistency and quality remained problems.

Not surprisingly, the best runs were retained for personal use or sold to neighbors. The rest was sold to distributors. To even out the quality and make what little good, aged whiskey they did obtain go further, distributors became rectifiers. The worst whiskey was rectified into neutral spirits, then blended with good, aged whiskey (maybe) and flavorings like sugar and prune juice. Glycerine was added for body. Acid was added to give it a good ‘burn’ going down. Some of the recipes were unhealthy and dangerous.

Bourbon purists thought the rectifiers were barbarians, but the argument generally revolved around labeling, specifically what should and should not be called whiskey. Rectifiers could and did make all sorts of false claims for their products, including false age claims. Though the claims were untrue, they were not against the law as there were no 'truth in labeling' laws like we have today.

The dispute came to a head when it was proposed that whiskey labels be regulated by the Federal Government under the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906. At first, the Act was interpreted to require that rectified products could not use the word whiskey without a modifier such as ‘imitation,’ ‘compounded,’ or ‘blended.’ Rectifiers were to be barred from using the term ‘bourbon,’ making age claims, or duplicating the labels of famous brands such as Old Crow and Old Grand-Dad, all of which were common practices.

The rectifiers were understandably appalled by this interpretation and attacked the bourbon interests for selling dangerous, unwholesome ‘fusel oil whiskey.’ Lengthy and rancorous hearings were held in the U.S. Congress, where whiskey quality was by no means an abstract concept.

This so-called 'Whiskey War' raged until 1909, when President William Howard Taft issued the ‘Taft Decision.’ Henceforth, rectified goods would be called ‘blended whiskey’ and the traditional product would be called "straight whiskey," but both had an equal right to the name ‘whiskey.’ Later, even more precise definitions were written for ‘bourbon,’ ‘rye,’ and other types.

Blended whiskeys were popular after Prohibition and again right after World War II, in both cases because straight, fully aged whiskey was in short supply. When more straight whiskey became available, the ratio shifted in straight whiskey’s favor. Blends are still sold today, of course. Seagram’s Seven Crown is the best-selling brand. Most blends are very inexpensive, found on the bottom shelf in 1.75 L plastic bottles. Blends have not benefited from the current whiskey boom.